Did You Know Kratom Isn’t New to America?

A Forgotten Leaf in the Colonial Pharmacopeia

A Leaf With a Long Voyage

Did you know Kratom isn’t new to America? Long before today’s headlines and debates, leaves remarkably like Mitragyna speciosa — the kratom tree — were already crossing oceans. In the 17th and 18th centuries, colonial apothecaries stocked crates of exotic barks and leaves brought by Dutch and Spanish ships from Southeast Asia. Some were named, some were not. Many were simply sketched and described by their effects.

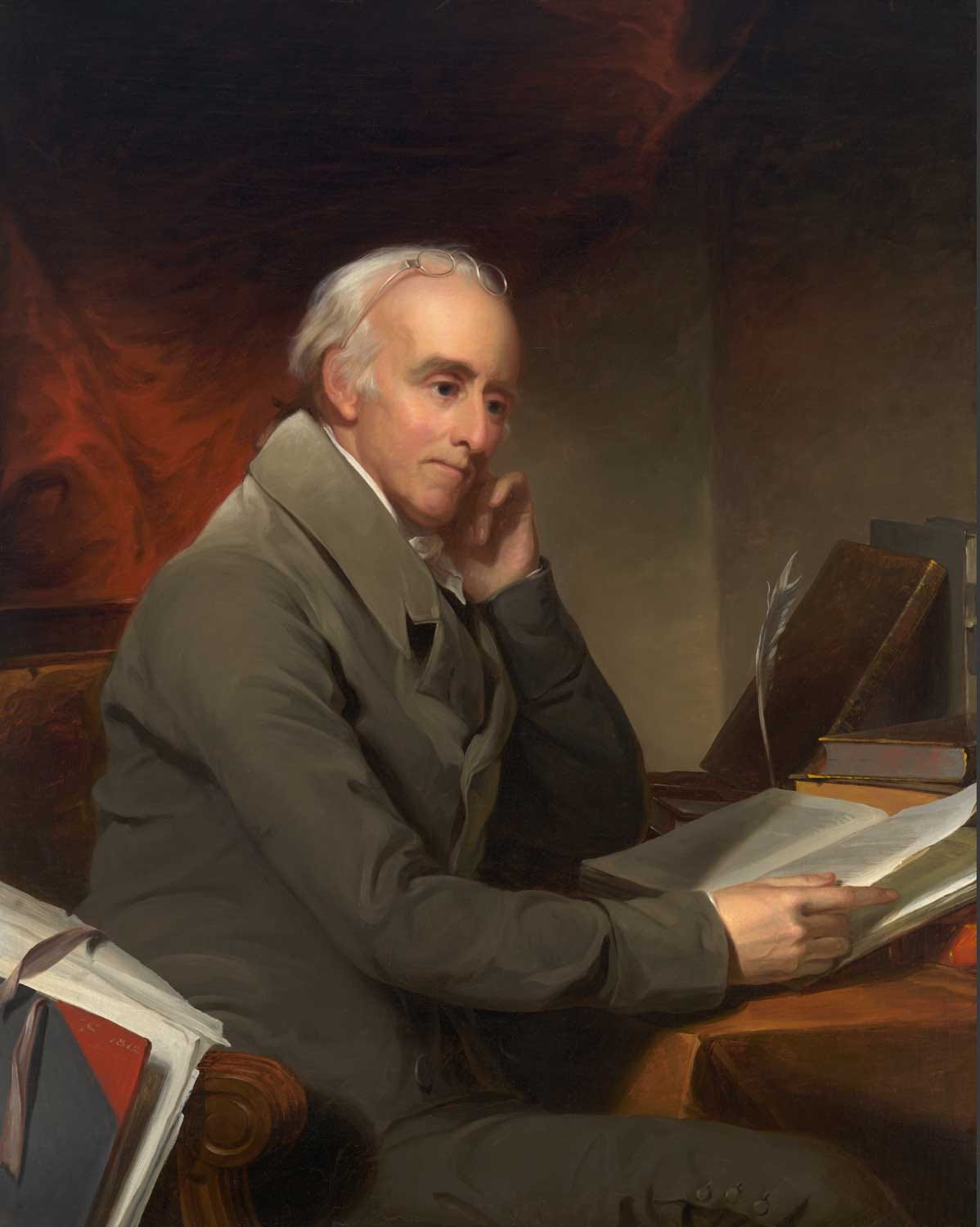

Among these “foreign leaves” were broad, glossy, deeply veined specimens — uncannily similar to kratom. Physicians like Benjamin Rush, America’s most famous Revolutionary doctor, used them. In one mastectomy case, Rush described giving a decoction of a bitter “Eastern leaf” to calm his patient. The leaf was unnamed, not yet a species in Linnaean taxonomy. But the sketch in his notes — oval, entire, and prominently veined — looks strikingly familiar.

The word “kratom” comes from Thai and entered Western usage in the 20th century. The plant itself was first given a scientific description in 1839, when Dutch botanist Pieter Willem Korthals classified it as Mitragyna speciosa in the coffee family.

🌿 What Kratom Is Today

Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa) is a tropical tree in the coffee family (Rubiaceae), native to Southeast Asia. Its leaves contain alkaloids — primarily mitragynine and 7-hydroxymitragynine — that act on the same opioid receptors in the brain targeted by morphine and oxycodone.

What It Does

Low doses: stimulant-like effects — alertness, energy, reduced fatigue.

Moderate doses: analgesia — relief from pain, muscle aches, some mood elevation.

High doses: sedative, opioid-like effects — drowsiness, euphoria, and in some cases nausea and respiratory depression.

Why It’s a Problem

Unregulated: In the U.S., kratom is sold in head shops, online, and gas stations as teas, powders, or capsules. Purity and dose vary widely.

Dependence risk: Regular use can cause dependence and withdrawal symptoms similar to opioids.

Toxicity & safety: High doses linked to seizures, liver injury, and rare deaths — often in combination with other drugs.

Regulatory limbo: The FDA warns against its use, but kratom is not a federally scheduled substance; several states have banned it, others allow sales with minimal oversight.

Why People Use It

Chronic pain management (as an alternative to prescription opioids).

Self-treatment for anxiety or depression.

Some use it to ease opioid withdrawal, though without medical supervision this is risky.

📜 The Colonial Pharmacopeia

Colonial medicine was a patchwork:

Willow bark for fevers,

Opium tinctures (laudanum) for severe pain,

Alcohol as universal anesthetic,

Cinchona bark (from Peru) for malaria,

Ipecac (from Brazil) as an emetic.

Into this came “leaves from the Indies,” imported in small amounts, brewed into teas. Enslaved Africans and Native healers experimented with them, while physicians noted their effects. Kratom may never have had the commercial pull of cinchona, but it was there — at least briefly — in the colonial pharmacopeia.

🖼️ What the Leaves Looked Like

Colonial doctors and naturalists rarely had perfect classification systems. They drew what they saw.

Kratom (modern sketch)

Coffea arabica (Coffee), 18th c. plate

Broad, shiny, opposite leaves with clear venation — remarkably close to kratom.Morinda citrifolia (Noni), 18th c. Indian drawing

Another Rubiaceae relative; thick, veined leaves.Cinchona officinalis (Quinine bark)

A Rubiaceae medicinal staple, widely recognized in colonial medicine.

Side by side, you can see why early colonists might have folded kratom into the same category of “bitter, foreign leaves” used to soothe pain and support endurance. Of course, they didn’t call it kratom - for them it was a medicinal leaf.

⚖️ Why Kratom Never Took Hold

So why did this leaf we call kratom fade, while cinchona and coffee became global commodities?

Supply: coffee and cinchona had monopolized trade routes; kratom never did.

Strength: Laudanum was stronger, Willow was familiar — kratom - or this leaf was somewhere in between.

Status: kratom lacked the prestige of Peruvian bark or the glamour of tea and coffee.

It was too mild for physicians chasing radical cures, too irregularly supplied for apothecaries, and too poorly classified to be canonized. It gave some relief but not enough.

🌿 A Lost American Leaf

Kratom in colonial America was never called kratom. It was “a bitter leaf,” “an Eastern tea,” a sketch in a notebook margin. But it was here — even if only briefly — and then it was gone.

Today, we debate kratom as if it’s a new arrival. In truth, it’s part of a much older story: the global migration of plants, the improvisation of colonial medicine, and the fragile line between what enters the pharmacopeia and what disappears.

🌱 A Note on Old Plants and New Lessons

As you can probably tell, learning about plants — especially those that shaped our early apothecaries and pharmacies — is a special interest of mine. I’ve already created a video series from the Chelsea Physic Garden in London, tracing the living history of medicinal plants that shaped colonial and Enlightenment medicine.

And I have another series coming soon, filmed during my recent travels, where we’ll explore more of these forgotten leaves and lost remedies. These videos will be fully available to our paid members, but most of them will also be available to our subscribers.

Because history isn’t just stories of people — it’s also stories of plants. And sometimes a leaf that looks ordinary, like kratom, carries with it a forgotten chapter in how we understood pain, endurance, and healing.