Particles to Plaque

How Heart Disease Starts, the process of atherosclerosis

An argument with a Carnivore

Why arguing about the word “cause” misses the biology — and what actually happens before a heart attack

Heart disease does not begin with a heart attack.

It begins quietly, invisibly, and over years.

This essay is Part One of a series on how atherosclerosis actually develops — not as a philosophical argument about causation, but as a biological process we can observe, measure, and interrupt.

I’m writing this because of a familiar interaction.

Recently, I had an exchange with a self-described carnivore enthusiast, who insisted there is no proof that ApoB causes atherosclerosis. When pressed, his objection wasn’t about experiments or anatomy. It was about the word cause itself. He argued that medicine uses the term incorrectly — that statistics don’t establish causation, and therefore LDL and ApoB cannot be causal.

This essay is not about him.

It’s about why this argument persists — and why it fails.

Oh and in the end of the discussion, he demanded I go to X (twitter) and apologize for telling people that ApoB is the cause of heart disease. Well, let us go into it.

Why this denial persists

There are people who deny that germs cause disease.

Some claim viruses don’t exist.

Others insist raw milk is harmless despite repeated outbreaks.

Medicine has always had to contend with denial.

Most of these beliefs are easy to dismiss, because the consequences are immediate. Bacterial pneumonia makes you acutely ill. Antibiotics make you better. Cause and effect are visible and fast.

Atherosclerosis is different.

You do not feel plaque accumulating.

You do not sense arteries narrowing year after year.

You experience the disease only after decades, when it announces itself as a heart attack or stroke.

That delay makes denial easier. It creates space to argue about definitions instead of mechanisms.

But slow biology is still biology.

The rhetorical dodge about “cause”

You will often hear this framed with some precision:

“You can’t say LDL or ApoB causes atherosclerosis. Statistics don’t establish causation. Risk isn’t cause.”

Parts of this are trivially true. Risk is not a thing. Hazard ratios don’t act on arteries.

But here is the sleight of hand: the argument quietly shifts from “risk is not a cause” to “nothing measured probabilistically can be causal.”

That leap is invalid.

Medicine does not establish causation through philosophical purity. If it did, we would have to abandon smoking as a cause of lung cancer, blood pressure as a cause of stroke, and hyperglycemia as a cause of diabetic complications.

Instead, medicine looks for convergence:

mechanism, necessity, dose over time, and what happens when you intervene.

Statistics don’t replace causation.

They tell us how often causal biology produces outcomes.

So let’s leave the word games behind and look at the biology.

First principles: what LDL actually is

Cholesterol is like oil or wax.

It does not dissolve in blood. If you had cholesterol freely in the blood, it would look like a container of vinaigrette - you’d see the blood as oil and water, but you don’t see that.

So the body packages cholesterol in this little protein pack called lipoproteins. They contain lipids, but are packaged in protein, so they don’t get that oil/water interface in the blood.

Cholesterol travels through the bloodstream inside lipoproteins. LDL is the dominant carrier. Each LDL particle contains exactly one ApoB molecule — an identifying protein that allows the particle to interact with cells.

Cholesterol does not cause disease by existing.

Disease follows when too many ApoB-containing particles circulate for too long.

That distinction — particle versus cargo — matters.

How LDL particles enter arteries

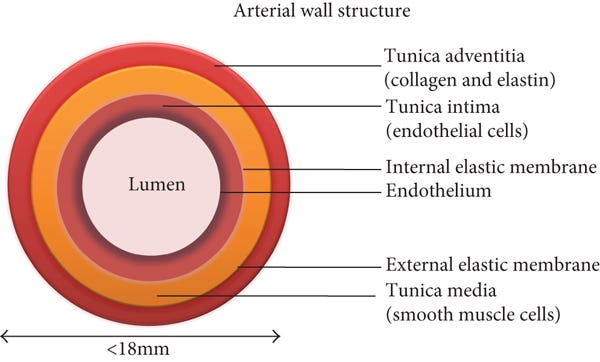

Endothelial cells line the inside of every artery. These cells are active, selective, and responsive to blood flow.

LDL particles do not leak through damaged vessels. In arteries, LDL particles cross the endothelium through active transport, a regulated process directly observed.

LDL receptors matter enormously — not because they are the primary transporters across the endothelium, but because they determine how many ApoB particles remain in circulation and for how long.

More particles in blood mean more endothelial encounters. The more LDL particles in the blood, the more they enter those cells, and the process of atherosclerosis is born.

If there are too many LDL particles in that endothelial cell, the cell will expell the particles into the non-blood side of the cell. So, once transported across the endothelial cell, LDL particles enter the intima — a narrow space beneath the endothelium where clearance is limited.

This is where atherosclerosis begins.

When particle burden is high

When LDL is “high,” what is high is particle number.

More particles mean more delivery into the arterial wall. At first, the system compensates. Over time, it cannot.

LDL particles accumulate. They bind to the arterial matrix, become modified, and are retained. Gradually, soft lipid-rich collections — atheromas — form.

This happens quietly, without symptoms.

No rupture.

No clot.

Just accumulation in a space never designed to store cholesterol.

The immune response: foam cells

Once LDL particles are retained and modified, the immune system responds.

Macrophages enter the intima to clean up what does not belong. They ingest modified LDL using scavenger receptors that do not shut off.

They keep eating.

Under the microscope, these lipid-laden cells appear foamy. That is why they are called foam cells.

This marks the first durable lesion of atherosclerosis.

The immune response is not the cause.

It is the response.

Why plaques form where they do

Atherosclerosis is not uniform.

Plaques form at arterial branch points and curves, where blood flow is disturbed and shear stress is low or oscillatory. Endothelial cells in these regions adopt an atheroprone state that favors LDL entry and retention.

Veins, exposed to different pressure and flow, are largely spared — unless they are placed into the arterial circulation, as in bypass grafts.

Same blood.

Same particles.

Different physics.

This spatial pattern is incompatible with the idea that atherosclerosis is merely “systemic inflammation.” It is entirely compatible with particle retention under arterial flow conditions.

Snapshots versus history

LDL levels can change quickly.

So can blood glucose.

But chronic disease reflects exposure over time, not a single measurement. Atherosclerosis integrates ApoB burden over decades.

This is why genetics matter.

People with lifelong low ApoB exposure — such as those with PCSK9 loss-of-function variants — develop little atherosclerosis. Those with impaired clearance accumulate disease silently from early life.

Short-term dietary shifts, viral anecdotes, or hospital lab values do not erase that history.

LDL also falls during acute illness, including heart attacks themselves. A “normal” LDL measured during or shortly after an event reflects stress physiology, not the exposure that produced the plaque.

Confusing snapshots with history is how rhetoric masquerades as insight.

Part One

Atherosclerosis begins with particles, time, and physics.

ApoB-containing lipoproteins circulate, cross the endothelium, become retained, and accumulate silently in the arterial wall. Over years, this process lays the groundwork for plaque growth.

This is Part One.

In Part Two, we will follow what happens next — how plaques evolve, destabilize, rupture, and ultimately become heart attacks and strokes — and how therapies that lower ApoB change that trajectory.

Words do not cause disease.

Biology does.

Paid Section — The Evidence Beneath the Narrative

Everything in the free section rests on observations that predate modern lipid trials and extend through contemporary molecular biology. In this section, I will anchor the narrative explicitly to the experimental and human evidence — not to argue philosophically, but to show where the story comes from.